Digital Futures for the Built Environment: highlights from the Landscape Institute's Digital Transformation and Integration event

What might the future look like for built environment professionals? How will innovation in emerging technologies, digital tools and data affect the way that landscape architects, urban designers, planners and architects design, plan, and build the cities and places of tomorrow? How could use of these novel tools support the realisation of better places?

These are some of the questions the Landscape Institute’s ‘Digital Transformation and Integration’ event explored in Bristol on 28 January 2020. The Landscape Institute (LI) is the chartered body for the landscape profession. Their ‘digital futures’ themed event included presentations, practical sessions, discussions and workshops by individuals and organisations at the cutting-edge of developing, applying, researching or refining the use of these digital tools for the built environment. The event focussed on three aspects in particular: the types of tools and technologies now available; their diverse applications for landscape and built environment professionals; and the future directions and potential these hold going forward.

This is a topic I am interested in as part of my SGSAH-funded PhD research at the University of Edinburgh, for which I am collaborating with industry partner Connected Places Catapult. My research focuses on the ways the use of innovative approaches and emerging technologies are disrupting the way we design and plan the built environment, and how these could best be harnessed going forward to improve the health, well-being and environmental outcomes of city places.

So, what new digital technologies and data tools are there?

From immersive environment technologies such as Virtual Reality (VR) and Augmented Reality (AR), to PropTech, Artificial Intelligence (AI) and machine-learning, digital democracy apps and web-platforms, use of drones, environmental sensors, 3D and 4D modelling and BIM, a huge range of emerging technologies and digital tools were discussed, demonstrated and explored at the Landscape Institute’s Bristol event. These might be used to provide additional layers of information during decision-making and planning processes, or as practical tools to improve and assist the design, planning and construction process itself.

How could they be applied in practice?

These digital tools and technologies have a range of potential applications within built environment professions, such as landscape architecture. Those discussed at the event included diverse applications from surveying the existing built environment or monitoring its construction using drones; to engaging communities via AR experiences they can actively create and participate in; to novel 3D and VR communication of proposed designs to elicit stakeholder feedback or to support iterative collaborative multi-disciplinary design processes; to improving pre-construction material/product selection via provision of environmental impact data (such as comparable embodied carbon scores) to enable informed choices at the point of specification. There was some brilliant discussion around all these potential contemporary applications and opportunities, as well as a number of likely future directions raised by speakers, in workshop discussions and throughout the day.

Alongside the exciting possibilities, several speakers and attendees also touched on cautionary notes in applying these technologies in built environment practice.

Echoing these concerns, I would argue that an increasingly pertinent question is becoming clear. How can the wealth of newly available technologies, tools and data be used in meaningful ways to create added value for those designing, planning, managing or constructing the built environment, as well as the citizens who then inhabit these spaces? In other words, how can these technologies be strategically used not just ‘because we can’, but to genuinely improve both the design, planning and construction processes, as well as the environmental and social outcomes of places? As Cedric Price famously said, “Technology is the answer, but what was the question?”. In a world increasingly saturated with newly available technologies and a wealth of data, it is more important than ever to start from a position of understanding what, as a society and a profession, the key challenges and problems we are facing are, and whether and how technological solutions might provide the most appropriate, effective, ethical, and inclusive solutions. As contemporary dicussions around ‘dumb cities’ attest - sometimes being ‘smart’ is about being ‘dumb’, and understanding where low-tech, established nature-based solutions may offer a preferable alternative.

So what could the future look like for the built environment professions? How might new technologies, digital tools and data-driven approaches be meaningfully used to change the way we design, plan, manage and occupy the places around us?

The LI’s ‘Digital Futures’ event featured an incredible lineup of presentations and workshops on related themes, many of which touched on probable future directions for the profession enabled via these technologies and tools. Speakers included Jacobs’ Andy Craven-Webb and Adam Dotlacil, Place Jam’s Mark Jackson, Vectorworks’ Katarina Ollikainen and Luca Stefanovic, Amalgam Models’ Chris Conlon, Streetlife, ACO’s Gary Morton & Olivier Bouzigues, University of Greenwich’s David Watson, Holotronica’s Hugo Stanbury, TreeWorks’ Luke Fay, LI Technical Committee’s Bill Blackledge, and Selux’s Norman Emery.

See below for seven particular future directions highlighted in event sessions by Alpha Property Insight’s Dan Hughes, AECOM’s Jon Rooney and Tom Roseblade, VIsioning Lab’s Dr Jessica Symons, Calvium’s Dr Jo Morrison, Knowle West Media Centre’s Zoe Banks Gross, RMIT University’s Dr Troy Innocent, Vestre’s Romy Rawlings, Keysoft Solutions’ Mike Shilton, and the Landscape Institute’s Steve Morgan and LI President Adam White. I thoroughly recommend viewing each speaker’s filmed presentation, available soon via the Landscape Institute website, to hear more about these in detail and their own words. I am also looking forward to being able to catch up with the other event presentations that ran concurrently, which I am sure will include valuable additions to the points below.

The seven likely future trends for the profession that stood out to me at the event were:

A move toward collecting data from physical places via sensors as part of increasingly connected and responsive governance systems. This will impact the built environment professions designing, planning, constructing and managing these spaces.

Increasing interdisciplinary collaboration will be needed between built environment professionals and the data scientists and engineers driving forward the technologies emerging from the ‘Fourth Industrial Revolution’.

Advances in AI, drones, sensors and other technologies are likely to assist with data collection and analysis stages of built environment professionals work, with humans still necessary to interpret and use the analysed data in ways meaningful for society and environment, and which link people, place and nature.

Digital, data and other emerging technologies offer opportunities for communities to find out more about their city and leverage positive change. Through use of co-design processes, skills training and participatory approaches these can reduce the exclusionary nature of some technology platforms.

Similarly, professionals can harness digital, data and other emerging technologies to expand the tools available in their work to help achieve a more accessible and inclusive built environment in ways that complement physical infrastructure improvements.

Digital place-making is emerging as a sub-discipline that combines people, place, technology and data to create more meaningful destinations and places for all, brings communities together, and can help citizens reimagine the urban environment in playful ways.

BIM as not only a tool to improve efficiency, reduce waste, and improve outcomes by testing scenarios in a virtual model before construction, but which could also help address the construction sector’s significant impact on climate change by enabling built environment professionals to make informed decisions when exploring design options and specifying materials based on whole project lifecycle carbon emissions.

Dan Hughes of Alpha Property Insight gave an overview of ‘PropTech’, including the ways technologies have been applied by the sector across previous decades, and how the prevalence of data and contemporary emerging technologies are now changing the way the built environment sector operates. As part of this discussion he highlighted a key anticipated future trend, as the move from collecting data primarily via online apps and web-platforms toward collecting data from physical places via sensors distributed prolifically throughout the urban realm. He argued this will have a significant impact on the professions that own, manage, design, build and curate these spaces, particularly with the advent of 5G. In agreement with Dan Hughes, AECOM’s Jon Rooney and Tom Roseblade discussed the potential for 5G and the Internet of Things (IoT) to support millions of wireless sensors across built environments, the data from which could enable AI decision-making about traffic flows, water management or air quality without the need for human intervention as part of an increasingly connected, responsive and efficient governance system. Indentally, AECOM’s 2019 ‘Future of Infrastructure’ report is both relevant to this topic and well worth a read.

Given the data, hi-tech and digital focus of the emerging technologies discussed, AECOM’s Jon Rooney and Tom Roseblade also discussed a key future direction as increasing collaboration between Landscape Architects and the built environment profession with the data and technology sectors, particularly data scientists. Their presentation related in particular to the Fourth Industrial Revolution - comprising data-driven approaches, cyber-physical systems, big data, increasing computing power, AI and machine-learning, high-speed connectivity (5G), blockchain and nanotechnologies. They then discussed what these technological advances might mean for the built environment profession in the context of continued urbanisation, a drive toward smart cities, increasingly connected infrastructure, and the circular economy. For example, blockchain could be utilised for digital contracts, 3D printing to reduce waste for complicated architectural forms, machine learning to identify different landscape elements for applications in tree cover canopy maps, and generative adversarial networks (GAN) to create increasingly realistic outputs of 2D imagery and 3D objects (e.g. Nvidia’s GauGAN which creates realistic landscapes from simple 2D sketches, and 3DGAN that creates 3D objects from 2D photos). Whilst potentially having a huge impact on our work, these technological approaches are not the core expertise of landscape architects. As such, interdisciplinary collaboration will be vital going forward to best realise outcomes for places that harness the opportunities technology presents, whilst ensuring the social and environmental impact of their use is beneficial.

Recurrent to several speakers’ presentations was a tension between how future work roles might best be divided between humans and new technological or computing capabilities such as AI. Dan Hughes of Alpha Property Insight highlighted the exponentially increasing quantities of data being produced globally the last few years, and the opportunities technological approaches present for automating data gathering and analysis processes, whilst finding purposeful ways for humans to play a role in the subsequent utilisation of the analysed data for positive social and environmental benefits that play to the strengths of humans. AECOM’s Roseblade and Rooney discussed concerns around ‘design by numbers’ that could result from technocratic approaches to understanding, planning and designing cities and places - giving the example of biodiversity net gain or ecosystem accounting. I found their emphasis that humans will still be needed to connect people, place and nature particularly insightful. This also relates to the aforementioned tension between what we can and will be able to achieve technologically in the future, and ensuring this is used in a socially meaningful way that delivers added value to humans and natural systems to address pertinent social and environmental problems. Carefully navigating this line will be critical going forward, and is something that Landscape Architects and other built environment professionals will increasingly find relevant to their work.

Addressing this concern, several event speakers examined the ways technologies are either being applied by built environment professionals to help address human user concerns related to the built environment, or as Zoe Banks Gross of Knowle West Media Centre discussed - can be used by citizens themselves as part of inclusive co-created approaches that may involve training/upskilling elements to reduce inequalities rather than further entrench these going forward.

Zoe Banks Gross’ presentation included examples of using digital, data and other emerging technologies via co-design approaches that engage communities, giving them the training and tools to find out more about their city and leverage positive change. I found her discussion of the importance of ensuring ‘digital accessibility’ - that digital tools, technologies, and web platforms (such as online mapping tools) should be designed for everyone, including those with any visual or audio impairment, or dyslexia, particularly inspiring and important. Zoe Banks Gross gave examples from the ‘Civic Tech’ LuftDaten citizen sensing air quality app, to ‘Our Digital City’, Bristol, which has been addressing the lack of digital inclusion through technology training in activities such as podcasting, smartphone film-making, or InDesign for jewellery making. This gives community members the opportunity to both learn skills and create positive change to address the challenges personal to them. This co-design approach, that often involves open sharing of data, is interesting when compared to the more technocratic ‘Smart Cities 1.0’ (as Dr Troy Innocent termed it in his presentation) approach whereby technology is employed in a top-down fashion by experts. Using technology as part of co-production turns this on its head, and ensures more socially driven notions of what a smart city might be (more in line with Dr Innocent’s description of ‘Smart City 3.0’). Zoe Banks Gross’ discussion of open data as characterised by being available to access, reuse and redistribute and the building block of open knowledge, was also insightful. She discussed various new platforms supporting access of open data, including Linux’s Community Data Licence covering the right to use and publish open data, which may enable more collaborate ways of sharing data relevant to the built environment in the future.

Digital tools and emerging technologies are also increasingly being used by built environment professionals to create more accessible and inclusive urban environments. This offers huge potential to improve the user experience of urban places for all residents, including those who are neuro-diverse or experiencing disability or accessibility constraints due to barriers presented by the existing built environment. Digital tools therefore offer potential to complement the essential physical changes to infrastructure required, that, to date, built environment practitioners’ work has more typically incorporated. Dr Jo Morrison of Calvium led a dynamic workshop discussion on this theme, based on Calvium’s excellent work and projects including NavSta, a mobile wayfinding system developed with Transport for London, Connected Places Catapult and Open Inclusion. Her inspiring workshop ‘Beyond the ramp: Using digital technologies to make the public realm more accessible, resulted in quick-fire ideation of potential concepts for utilising digital tools to improve urban user experience for particular user groups’ concerns of crowded spaces. For example, fear of being knocked or experiencing anxiety in busy pedestrian areas such as train stations. Dr Morrison argued we need to go ‘beyond the ramp’, and not just think about one mode of wheelchair access, but harness all the tools currently at our disposal to improve the built environment for all through genuinely inclusive design. Other workshop examples discussed included Neatebox, whose Button app used via a smartphone or watch to press pedestrian crossing buttons addresses the issue of inaccessible crossings for a person with a mobility or visual impairment.

Digital Placemaking was also discussed as a future direction, emerging discipline, and means of engaging citizens and community in their local places. Several speakers focussed on this concept, each with a slightly different focus. For example, Dr Jessica Symons of VisioningLab discussed their use of AR routes and experiences created by citizens as part of co-created methods of engaging people in place, sharing their local knowledge, values or insight. Particularly interesting were the learnings and strategies shared from VisioningLab’s work to date, including a recommendation for AR rather than VR for community engagement due to practical considerations (limited VR headsets causing queues, tripping over bags), as well as ethical (VR can create false memories for children). As well as to carefully consider the narrative opportunities and potential of the medium when choosing a technology to employ for engagement purposes.

Dr Jo Morrison of Calvium described Digital Placemaking as centred on the understanding and interrelation of people, place, technology and data to create bespoke location-based digital solutions that create more meaningful destinations for all. She argued this approach can operate across planning, design, implementation and management of the built environment. For example, Calvium created a heritage trail wayfinding app for the first phase of the Battersea Power Station development, to activate this place as part of the process of urban regeneration. The app incorporated image-recognition triggers for AR visuals and location-based audio, created by a collaborative team of professional storytellers, historians and community members. I found Dr Morrison’s points about the motivation for using AR as a considered, meaningful and appropriate choice because of the value it added to the experience and activation of this place particularly interesting. Calvium’s work has also included use of haptic digital tools to bring to life the Lost Palace of Whitehall for Historic Royal Palaces through an audio tour featuring curated sounds triggered by proximity sensors from an object carried by the user. This example highlighted the ways emerging technologies can be used in digital placemaking that focus on senses including sound and touch, rather than necessarily sight-dominated use of AR (or VR) experiences.

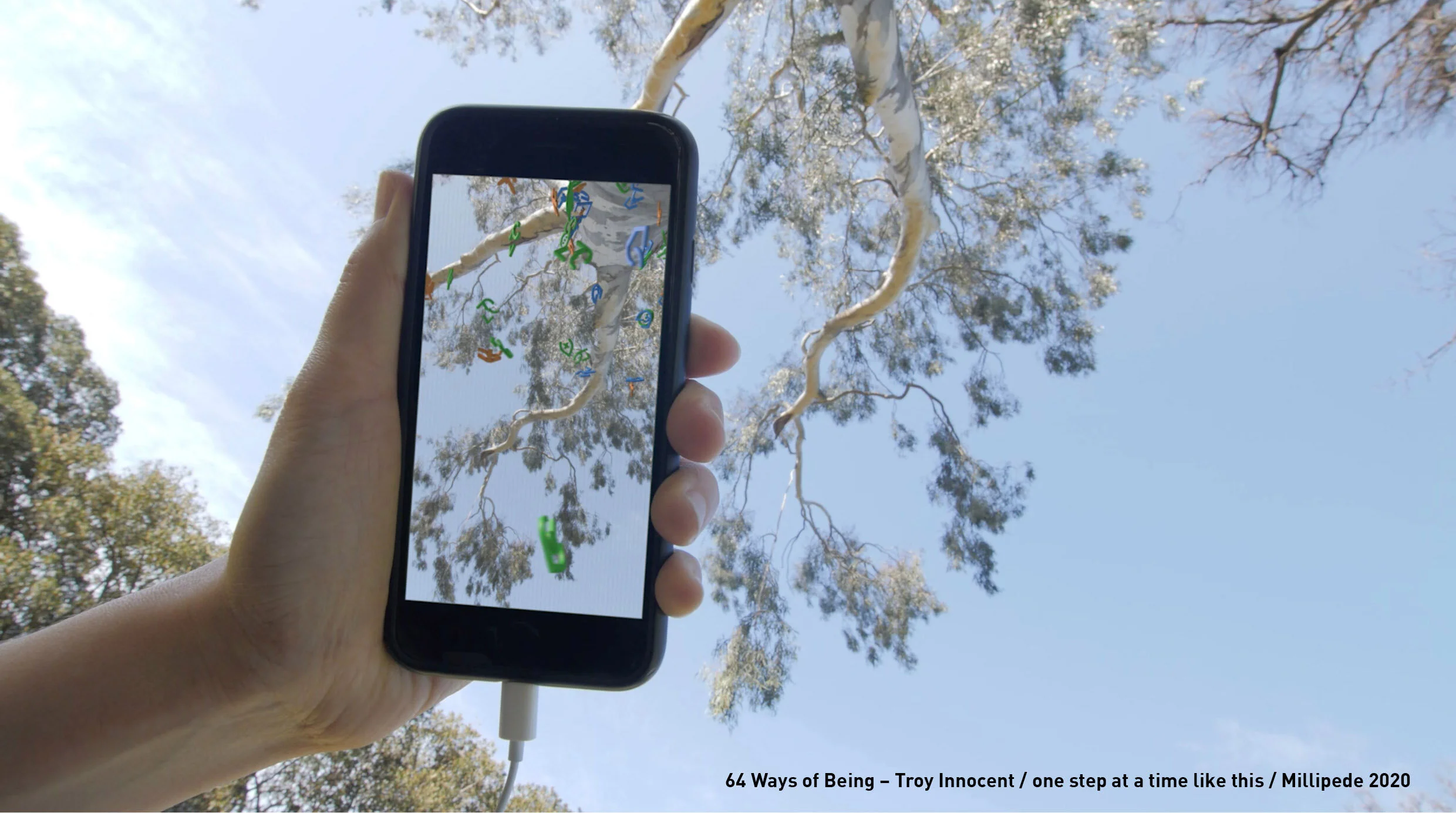

The role of Digital Placemaking in the future of ‘playable cities’ and ‘smart cities’ concepts is also important. Dr Troy Innocent, a VC Senior Research Fellow at RMIT, urban play scholar and artist game-maker referenced Boyd Cohen’s three generations of Smart Cities, and how the ‘smart city’ concept has evolved to include more socially driven and co-created, participatory approaches from its technocratic origins, to argue that ‘smart cities 3.0’ is essentially a ‘playable city’. This demonstrates the success of the playable cities movement as a viable alternative to the technological determinism of earlier iterations of the smart city concept. Dr Innocent’s presentation and work focussed on ‘playable cities’, including the use of AR combined with public art as a digital storytelling and place-making tool, bringing together communities to transform their experiences of the urban environment. For example, Wayfinder Live is a multi-player game which incorporates AR experiences triggered by pieces of visually stunning abstract geometric public art that act as ‘urban codes’ (similar to a QR code) within the physical environment. Together, these create a route for traversing, exploring, and reimagining experiences of the city via these key destinations. Similarly, Accelerando - a playful transformation of Melbourne’s public transit infrastructure, launched in 2018, uses public art displayed on the surface of a tram and links this to a downloadable app that creates variable musical scores dependent on the tram’s speed whilst moving past participants’ mobile phone screen. Currently, Dr Innocent is also involved in developing ‘64 Ways of Being’ - a new collaborative platform merging alternative experiences of public spaces. These projects enable the reimagination of the city, whilst fostering connection through co-production and collaboration, and a sense of discovery and joy through their playful exploratory nature. I found particularly interesting Dr Innocent’s comments and practical learnings, including the sparing use of AR - achieved by using it where it adds value only and limiting the time needing to view AR via their phone screen - as a way of ensuring participants do not lose out on connecting with the urban environment in front of them.

Another future direction discussed, was the potential for BIM to help reduce the construction sector’s significant carbon emissions. Keysoft Solutions’ Mike Shilton and Vestre’s Romy Rawlings discussed how BIM can be used collaboratively by multi-disciplinary built environment design teams to help model and make informed decisions when designing and specifying materials to reduce carbon emissions across the whole lifecycle of a project. They argued that the climate emergency presents an opportunity to move from damaging short term thinking and value engineering based on cost, to a more considered lifetime design approach that allows the environmental impacts of different decisions to be modelled and considered. To support BIM and digital modelling of built environment projects, Shilton and Rawlings also discussed the ways that technologies such as drones are being used for surveys, 3D scanning, and monitoring of construction sites to cuts down from site-visit related carbon emissions. Other trends include 3D printing and ‘additive design’ - whereby prototypes can be printed directly from the 3D digital model to improve designs and reduce errors, in resource-efficient ways using minimal materials due to creation of a rigid structure incorporating gaps. Equally, increasing fabrication off-site is allowing manufacturing-based efficiencies to be applied to construction processes, including reducing waste materials and improved health and safety outcomes compared to on-site construction. These discussions and trends demonstrate the value of BIM and digital models in creating a comprehensive ‘digital twin’ of a project, that enables scenario-testing, mistakes and exploration of different project variables digitally, so this can be ‘got right’ in the model before building a project in the real world. As such, Shilton and Rawlings argued BIM offers “a measured and effective way of tackling carbon reduction in collaboration with other built environment professionals”. Harnessing digital tools and technologies in this way to reap multiple benefits - both in terms of efficiencies for professionals, improved project realisation and wider environmental outcomes as a ‘win-win-win’, is likely to be significant in changing ways of working for built environment professionals and our environmental impact as a sector into the future.

It is clear that digital tools, technologies and data-driven approaches offer a great opportunity for the built environment professions - if harnessed appropriately - for supporting the design, planning, construction and management of great places, both for people and environment. The Landscape Architecture profession is evolving and adapting to incorporate these skills and approaches, and, as President of the Landscape Institute Adam White emphasised - seems well placed to bring together interdisciplinary teams that can utilise the technological advances available to us in a way that delivers better places for all.